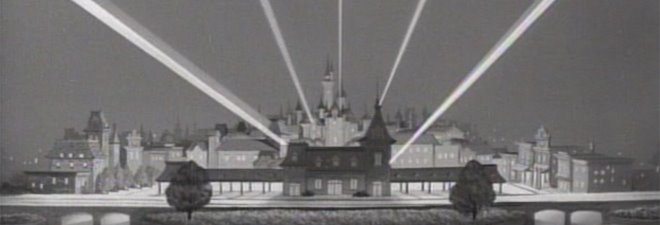

Early concept drawing for the Dolphin

(c) Disney

The Swan and Dolphin Resorts at Walt Disney World. For a couple of chain hotels, there’s certainly been a great deal written about these buildings.

Back in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, when Disney was on an expansion bender, the Swan and Dolphin were emblematic of the new way things were being done at the Mouse House. Michael Eisner and Frank Wells were on a mission. For six decades, Walt Disney Productions accumulated an amazing array of assets and then, inexplicably, allowed them to sit fallow. The new team was here to leverage those assets, pronto.

At Walt Disney World, that meant exploiting the thing they had plenty of: LAND! Disney had plans for that land and was building like mad. The goal was to keep its current customers longer and to attract a new clientele—all while wringing visitors’ pocketbooks tighter than ever before. An explosion of new hotel rooms was just beginning. It was a key part of the new regime’s money-grab strategy.

Of course, the description above is pretty snarky, if not downright cynical. It also isn’t fair. Because, in spite of the ugly way Michael Eisner’s time at Disney ended, there really was a lot of finesse to his expansion program. In the case of the Swan and Dolphin, that finesse came in two main forms.

The first is the most conspicuous: the architecture of the Swan and Dolphin.

Unlike previous large scale hotels like the Polynesian Village or even the Contemporary—both of which plopped guests into hyper-realized fantasy locales in much the same way as the Magic Kingdom’s themed lands—The Swan and Dolphin refused a representational thematic approach. They also are not the “glass and brass” buildings found across from the Orange County Convention Center and throughout the United States (it’s worth noting that fact, as Tishman Realty’s original contract with Disney allowed them to build that sort of uninspired hotel structure as part of this development).

Instead, Eisner set himself on a hiring-spree, engaging the services of so many high profile “starchitects” that his mania warranted an article in a 1991 issue of Time Magazine. For these new Florida hotels, Eisner chose an architect who was fresh off a previous Disney commission, Michael Graves.

Back in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, when Disney was on an expansion bender, the Swan and Dolphin were emblematic of the new way things were being done at the Mouse House. Michael Eisner and Frank Wells were on a mission. For six decades, Walt Disney Productions accumulated an amazing array of assets and then, inexplicably, allowed them to sit fallow. The new team was here to leverage those assets, pronto.

At Walt Disney World, that meant exploiting the thing they had plenty of: LAND! Disney had plans for that land and was building like mad. The goal was to keep its current customers longer and to attract a new clientele—all while wringing visitors’ pocketbooks tighter than ever before. An explosion of new hotel rooms was just beginning. It was a key part of the new regime’s money-grab strategy.

Of course, the description above is pretty snarky, if not downright cynical. It also isn’t fair. Because, in spite of the ugly way Michael Eisner’s time at Disney ended, there really was a lot of finesse to his expansion program. In the case of the Swan and Dolphin, that finesse came in two main forms.

The first is the most conspicuous: the architecture of the Swan and Dolphin.

Unlike previous large scale hotels like the Polynesian Village or even the Contemporary—both of which plopped guests into hyper-realized fantasy locales in much the same way as the Magic Kingdom’s themed lands—The Swan and Dolphin refused a representational thematic approach. They also are not the “glass and brass” buildings found across from the Orange County Convention Center and throughout the United States (it’s worth noting that fact, as Tishman Realty’s original contract with Disney allowed them to build that sort of uninspired hotel structure as part of this development).

Instead, Eisner set himself on a hiring-spree, engaging the services of so many high profile “starchitects” that his mania warranted an article in a 1991 issue of Time Magazine. For these new Florida hotels, Eisner chose an architect who was fresh off a previous Disney commission, Michael Graves.

Model of The Walt Disney Company corporate

headquarters in Burbank

Graves and his team conceived the Swan and Dolphin storyline* and custom-designed everything, down to the detail of the hotels’ carpet patterns and the plates used in restaurants throughout the complex. The end result was strikingly different to anything that had ever come out of Disney before. It had a different scale and a lavish attention to detail. And it had the gravitas of being praised by architecture critics—something unusual for a company whose very name was often used as a prejorative among the Inteligencia.

Graves's designs for room furnishings in the hotels

(c) Disney

The second bit of finesse Eisner employed with the Swan and Dolphin is only slightly less apparent, but far more impactful: the hotels’ siting on Disney property and the subsequent development of this new expansion area.

When Walt Disney World debuted in 1971, it featured a Disneyland-style theme park buried deep within the Central Florida wilderness. This Magic Kingdom anchored a sprawling Seven Seas Lagoon that featured two large hotels, each one serving Disney’s guests and framing the Walt Disney World experience. This was Phase One, a world of its own, seemingly-complete, right down to the white sand beaches, man-made waves, and monorail-themed cocktails.

Flash forward eleven years later to the opening of EPCOT Center. For the billion dollars spent to create this massive project, absent was the peripheral development found along Phase One’s lagoon. For the entirety of the 1980’s, EPCOT Center, the harbinger of the world of tomorrow, stood alone in its swamp, miles distant from the Hawaiian luaus, buzzing watercraft, and hotel rooms that surrounded the Magic Kingdom and meant money in the bank for Disney.

The Eisner and Wells team wasn’t the first to acknowledge this omission and propose a remedy. Disney’s previous chairman, Ray Watson, had approved the Tishman Realty deal with the same objective in mind. But the new team’s approach was bold in the same way Graves’ aesthetic was bold. The location of the project would change. As Joe Flower noted in his Eisner biography Prince of the Magic Kingdom, the new hotels would be placed at the physical center of the WDW property, its “center of gravity.” Which nestled it in between EPCOT Center’s World Showcase and the then-under construction Disney-MGM Studios.

When it opened, this new development—anchored to its south by The Swan and Dolphin and their shared Crescent Lake—transformed the EPCOT Center experience. No longer was the park some hard-to-access offshoot that committed guests to travel by automobile, bus, or a convoluted monorail exchange just to experience its offerings. In fact, EPCOT Center was in many ways now the most accessible park for the guests staying at the Swan and Dolphin. You could get to the park by a Friendship launch, or a tram, or even by foot. And you’d enter through an exclusive backdoor, cleverly positioned near the park’s many acclaimed restaurants.

Even more importantly, the entire Walt Disney World property was transformed by this new development. As the Yacht and Beach Club hotels and, later, the Boardwalk Inn opened as part of the same area, the Florida resort now had two bustling mixed use centers, each with its own unique attitude and offerings, and potential for growth. With the Swan and Dolphin’s enormous convention facilities and the unique EPCOT Center tendency to attract adults, Disney imagined building a second nighttime entertainment facility in the area, similar to Pleasure Island.

Satellite view of the Swan and Dolphin Resort and the Crescent Lake developmentthat today connects Epcot and Disney's Hollywood Studios.

It was all so good. And it was successful to boot, attracting guests and keeping them at Disney just as intended. So why then the title of this article? Why are these the most vile, unredeeming hotels ever built—ever?

If you’ve read this far, you already know the answer. Because, for many Disney fans, these hotels represent a cardinal sin, an offense to a key tenet of the Walt Disney Methodology for Creating Entertainment Spaces. The Swan and Dolphin are distractions. They violate the rhythm, landscape, and illusion of EPCOT’s World Showcase. They are visual intrusions.

It’s pretty easy to find fault with the Swan and Dolphin, looming as they do over World Showcase’s southwestern attractions. There is no sense to it, no logic that explains why a stylized pyramid and a colossal gang of classically-inspired (but oddly cartoonified) water creatures would occupy the same horizon line with hyper-realized replicas of real-world landmarks. Japan’s castle, Morocco’s minarets, and even Eiffel’s Tower are all made diminutive, living like doll houses under the shadow of these post modern monstrosities.

If you’ve read this far, you already know the answer. Because, for many Disney fans, these hotels represent a cardinal sin, an offense to a key tenet of the Walt Disney Methodology for Creating Entertainment Spaces. The Swan and Dolphin are distractions. They violate the rhythm, landscape, and illusion of EPCOT’s World Showcase. They are visual intrusions.

It’s pretty easy to find fault with the Swan and Dolphin, looming as they do over World Showcase’s southwestern attractions. There is no sense to it, no logic that explains why a stylized pyramid and a colossal gang of classically-inspired (but oddly cartoonified) water creatures would occupy the same horizon line with hyper-realized replicas of real-world landmarks. Japan’s castle, Morocco’s minarets, and even Eiffel’s Tower are all made diminutive, living like doll houses under the shadow of these post modern monstrosities.

It’s a collision between two worlds that do not belong together and it should never have happened. Themed spaces should be kept singular and uninterrupted by competing elements. Visual intrusions shouldn't exist in a well-designed themed attraction.

Actually, I don’t believe that. In fact, I think that reaction is far too prevalent in contemporary theme park design, especially at Disney. And I think it sucks.

Stay tuned for Part 2 and I’ll explain why…

*Werner Weiss unfolds the premise behind The Swan and Dolphin’s design in a wonderful article that reveals the truth behind one of my favorite WDW urban legends AND has a picture of a helicopter!

Actually, I don’t believe that. In fact, I think that reaction is far too prevalent in contemporary theme park design, especially at Disney. And I think it sucks.

Stay tuned for Part 2 and I’ll explain why…

*Werner Weiss unfolds the premise behind The Swan and Dolphin’s design in a wonderful article that reveals the truth behind one of my favorite WDW urban legends AND has a picture of a helicopter!

1 comment:

They can't all be the Saga Inn during a cheerleading expo, can they...?

Post a Comment